For those who are interested in the history of the dances, here are two articles. The first was written in 1990, the second article in 2015, so it is up-to-date and gives a fuller account as it includes the more recent 25 years or so.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the dances in 1968, a timeline giving an in-depth look at the development of the dances was written, which you can read here.

We Circle Around – A Short History of the Dances

By Neil Douglas-Klotz

[written in 1990]

“We circle around, We circle around, the boundaries of the earth, the boundaries of the earth….”

The words of the Arapaho Ghost Dance echo through a hall crowded with people who sing, hold hands and move in concentric circles. Like the original Ghost Dancers, these dancers focus their movement and voices on bringing peace and justice to earth. The folk dance that they do is a collaborative creation of Native American elders and whites. It is one of 300 or so Dances of Universal Peace which invoke all the major traditions of humankind – a non-elitist form of sacred dance that aims to bring ‘peace-movement’ to the planet.

Over the last two years (1988-89) the Dances travelled to, and took root in, the U.S.S.R., bringing Soviets and Americans together, singing and dancing in celebration of cultural diversity and world peace. Since their founding 22 years ago in San Francisco, the Dances of Universal Peace have been shared in groups throughout the English-speaking world, Costa Rica, Mexico, Holland, Switzerland, Germany, France, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Pakistan and India. As they spread, they bring an experience of praying and dancing in celebration of diversity and in honour of the unity of all creatures.

As a form of ‘art for peace’, the Dances have their origin much earlier in the work of three mystics: two Americans and an Indian who looked behind the wars and rumours of war that they saw in the 1920’s to find a deeper basis for peace and global security. From their early work, the Dances of Universal peace have developed, not only as a visible ‘peace demonstration’, but also as a form of therapeutic movement re-education, a way to heal the personal as well as global roots of war and peace.

The Goose-step and War.

“Metaphysically, the goose-step and war are one. It makes use of force without stint or qualification. It involves destructive psychic as well as physical forces. To abolish war we must abolish war-like movements.”

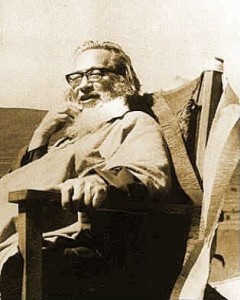

In 1939, the founder of the Dances of Universal Peace, Samuel L. Lewis, wrote these words as he contemplated the inner realities of sacred dance and its uses in the service of world peace. He was ahead of his time in such thoughts. Lewis, born in 1896 in San Francisco, had early been rejected by his family for an over-avid interest in religion (his father wanted to install him in business) and had studied theosophy, Eastern religions, and the mystical side of his own religion, Judaism. To this end, he sought out and found a wide range of genuine teachers of Buddhism, Vedanta, Yoga and Sufism who made their way to the USA during the teens and early twenties. During this time, he also studied sacred dance with American dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis (also the teacher of Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey and others).

After reconciling with his father on his deathbed, Lewis received a small inheritance while in his 50’s. He finished college with a degree in horticulture and set off on two trips to the East to share the latest in organic farming techniques, as well as in search of genuine mysticism. The story of these trips to Japan, India, Pakistan, and Egypt is told in the book of his selected diaries, Sufi Vision and Initiation.

The journeys were pivotal in Lewis’s life. Rejected as an ‘eccentric’ at home, on his one-man citizen diplomacy mission, Lewis received welcomes everywhere from heads of state to the street children for whom he danced. He found that the professors of agricultural colleges were under intense pressure to convert to ‘modern Western’ methods, which were fatally tied in to petroleum based economies and sterile seed sources. They were enthusiastic about the information and seeds that Lewis pulled from his suitcase. On his search for genuine mystics, Lewis found scientists, scholars, government and professional people at all levels who were practitioners of Zen, Sufism, Vedanta, mystical Christianity and other traditions, but who had been overlooked by Western scholars because they were living what appeared to be ‘normal lives’.

A “Dance of Universal Peace”.

Lewis felt confirmed in his early intuition that real religion must be practical and express the deep unity that is found behind all traditions. While at the tomb of a Sufi saint in India, he had a vision of a ‘Dance of Universal Peace’, which would combine mystical practice with a body-based reality of world peace. In his later diaries, Lewis spoke of his understanding of the oft-used word ‘peace’:

“Words are not peace. Thoughts are not peace. Plans are not peace. Programs are not peace. Peace is fundamental. It is easy to prove in the sciences, and the real spiritual masters who are here are teaching it. It is fundamental to all faiths, all religions, all spirituality. It is from this that everything was, or let us say: In the beginning was Peace and the Peace was with God and the Peace was God, and out of this Peace has everything been made that was made.

The difference between this Logos-Peace and what we generally call “peace” is that the latter is a vacuum, a zero, a nothing, a blank, a negative to the extreme. The Logos-Peace is fullness, all- inclusive, and expresses the human family. The human body is a society of myriad cell units working together. The totality of humanity (‘Adam’ in Hebrew) is a society of myriad personalities which must work together in and with and under God. Only this must be experiences and not syllogism, truth and not truism. Every transcendentalist poet of America knew it, every newsman seems to work against it we must have excitement. Excitement is the death of peace. I have my poetry, and the Dance of Universal Peace.”

The Grandmother of the Dance.

Upon his return from the East, Lewis dedicated the first Dance of Universal Peace to his sacred dance teacher, Ruth St. Denis, then in her late eighties. A sensation in her early years with individual dances like ‘Radha and Incense’, Ruth St. Denis entered the inner realisation of the figures of divinity that she chose to perform like Mary, Kwan Yin, the Yogi, O-Mika and others and from that feeling danced a vision of perfection. By choosing figures from many different cultures, Ruth St. Denis presented a wordless show of unity before thousands of audiences all over the world throughout her life.

With her partner Ted Shawn, she also founded one of the first schools of modern dance in America, called ‘Denishawn’. Because most of her writings on dance were mystical in nature, she has met with little understanding or favour among contemporary dance historians, who largely overlook her role in creating (along with Isadora Duncan) the first Western modern dance.

When her style of dance fell out of popular favour, Ruth St. Denis retreated to the further investigation of her first love sacred dance. Among other things, she wished to find a group form of dance that would be easily accessible to non-performers and which would communicate the deep feelings of unity and peace that she had felt in individual performances. It was here that she found a collaborator and apt student in Samuel Lewis.

In her unpublished book The Divine Dance (1933), Ruth St. Denis wrote of her vision of a future dance for life and peace:

“The dance of the future will no longer be concerned with meaningless dexterities of the body…. Remembering that man is indeed the microcosm, the universe in miniature, the Divine Dance of the future should be able to convey with its slightest gestures some significance of the universe…. As we rise higher in the understanding of ourselves, the national and racial dissonances will be forgotten in the universal rhythms of Truth and Love. We shall sense our unity with all peoples who are moving to that exalted rhythm.”

The Unity of Religious Ideals.

Ruth St. Denis was overjoyed with the promise of a universal sacred folk dance that Lewis presented to her. A few years later, Samuel Lewis, then in his seventies, found a group of people who were willing to embody his vision of dance: the young people and hippies of the late sixties in San Francisco.

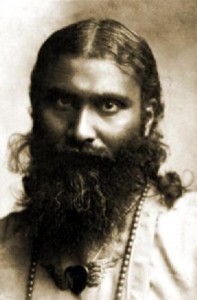

Along with his Dances, he presented a universal approach to the teachings of Buddhism, Hinduism, Sufism, Christianity and all religions and became known as ‘Sufi Sam’. Lewis states in his diaries that the other major influence on the Dances of Universal Peace was his first Sufi teacher, Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882 -1927). Hazrat Inayat Khan presented a vision of the ‘Unity of Religious Ideals’ that became a foundation for the Dances and the means of including an ever widening world of traditions that are celebrated.

For Hazrat Inayat Khan, it was important that the issue of religious strife be acknowledged, not swept under the rug with a sort of bland agnosticism or a philosophy that ignores the importance of the religious idealism in life. He wrote:

“Whenever there has been a war…we always see the finger of religion. People think that the reason for war is mostly political, but religion is a greater warmonger than any political ideas. Those who give their lives for an ideal always show some touch of religion. The religious channel in Sufism exists in order to avoid greater catastrophes, and to gather together the followers of different religions in the understanding of the one truth behind them, so that they may hold in respect all the teachers of humanity who have given their lives in the service of truth. Instead of doing as the theologians in colleges who only want to find what is the difference between Moses and Buddha, one should look behind all religions to see where they unite, to find out how the followers of all the different religions can be friends.”

In addition, Lewis had learned from Hazrat Inayat Khan the Sufi science of the mysticism of sound, which enabled him to choose phrases for the early Dances which filled the body with resonance and with a genuine feeling for each tradition celebrated. For this reason, he credited both Ruth St. Denis and Hazrat Inayat Khan with providing him the ‘keys’ to the creation of the Dances. Lewis’s collaboration with Hazrat Inayat Khan’s son, Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, also proved instrumental in bringing the Dances out of their visionary state and into actuality.

Still a Dance of the Future

After Lewis’s passing in 1971, the Dances continued and, because they were often passed by word of mouth, sometimes became confused in both feeling and form. At one point, any vaguely circular form of group dance with chanting became known as ‘Sufi dancing’, whether those leading them were Sufis or not (and whether they were moving in rhythm or not – the definition of “dancing”).

On the positive side, there was an emphasis on simple movement with feeling and thought united. On the negative side, the form was (and still is) sometimes imitated without the necessary training, background or awareness. An international Dance network was established to alleviate some of these difficulties and provide access to skills and teaching materials for those who wish to share the Dances in their communities.

As more and more people have studied and attuned to the form, new Dances continue to be created and their uses have widened from peace studies classes to work with the mentally handicapped.

The Dances continue to grow for several reasons:

l. The feeling of chanting simple, sacred phrases with devotion in English, Greek, Latin, Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, Sanskrit and many other languages gives, especially when combined with movement, an immediate, accessible feeling for another tradition. That same feeling may also, as Lewis stated, unearth the forgotten and rejected places within our own cells and psyches.

2. The Dances use simple folk movements drawn from the world’s traditions and generated from the feelings of the phrases. The folk movements create a feeling of solidarity and unity. In addition, free movements are used within some dances to allow one to ‘re-create’ one’s own authentic movement within the support of the group movement. As contrasted with traditional dance therapy, this is a more effective way to allow participants to experience new creativity and freedom in the body than the elusive exploration of habitual movement and personal neuroticism.

3. The Dances are non-elitist, take no special training and can be done by almost anyone – they have even been done by those in wheelchairs. The miracle of group feeling and joy of the dance is available to ‘non-dancers’.

At the same time, the form lends itself to increasing refinement of movement, feeling and body awareness as one simultaneously discovers more of oneself-and more of the world. Combined with forms of walking meditation and exploration that Lewis began, the Dances lead to a confrontation with and acceptance of more and more of one’s true self. This is ‘peace and security’ on a body level.

Samuel Lewis envisioned that forms like the Dances of Universal Peace would become the future of the arts emphasising group unity rather than the adulation of individuals, process rather than product. He wrote in 1939:

“The Dance is the way of life; the Dance is the sway of life. What life gives may be expressed with body, heart and soul to the glory of God and the elevation of humanity, leading therein to ecstasy and self-realisation. VERILY, THIS IS THE SACRED DANCE.”

“When doctrines divide and ‘isms’ turn human against human , without speech, without silence, let us demonstrate. Let these demonstrations manifest everywhere. Not what we think or say but what we do shall avail…. On with the dance!”

This second article was also written by Saadi Neil Douglas-Klotz, but in 2015.

History of the Dances of Universal Peace Organization and

the Mentor Teachers Guild

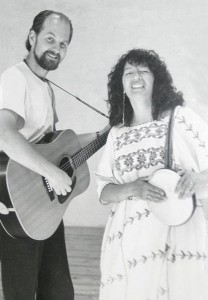

Dances of Universal Peace International has undergone several transformations over the past 33 years. Its first incarnation was co-founded in 1982 by Saadi Neil Douglas-Klotz and Tasnim Hermila Fernandez, two teachers from the Sufi Islamia Ruhaniat Society and the Sufi Order in the West respectively. As it was then called, the Center for the Study of Spiritual Dance and Walk was set up as a project of Khankah S.A.M., the Sufi community in San Francisco, CA centered around the former home of Murshid Samuel L. Lewis. The Center provided an on-site, live-in training program for those who wanted to study the Dances and Walks intensively in month-long modules.

Within a year, the project had broadened considerably and become the Center for the Dances of Universal Peace, subtitled ‘a network and resource center.’ Based in Fairfax, California, the Center sought to connect Dancers and Dance circles around the world and provide training resources to them through printed materials and in-person retreats in various regions. During this phase and until 1988, the Center was a project of the Sufi Islamia Ruhaniat Society (SIRS), with the blessing and encouragement of the spiritual director and Pir of the Ruhaniat, Moineddin Jablonski, the spiritual successor of Murshid Samuel Lewis. The Center published a number of Dance notation booklets with recordings and kept a database of Dance teachers and regular circles (on a primitive—by today’s standards—computer). It also produced a quarterly newsletter and published a much-expanded update of the book Spiritual Dance and Walk: An Introduction.

During this period, the Center sponsored the first camps solely dedicated to the Dances and Walks, and training in them. The first such camp was held at Lama Foundation in New Mexico in August 1984 with Tasnim and Saadi as the main teachers. Key people who volunteered their help for the Center in this phase were: Ardvisura Carol Griffin, Malika Merrill and Kamae A Miller. An early board of advisors (which later became the first board of trustees) was set up which included: Mansur Rodney Kreps, Victoria Darvesha MacDonald, Salt Swan, Ellen Fietz Hall, Ardvisura, Malika, Kamae, Tasnim and Saadi.

In 1988, the Center sought its own non-profit, tax exempt status as an arts and service organization, adding PeaceWorks to its name. The idea was to access greater avenues of funding for helping the Dances spread beyond the Sufi community in which they had been birthed. However, the Center always maintained a close relationship with the SIRS. As Pir Moineddin wrote to the Ruhaniat Board of Trustees at the time:

“The organizational and legal bifurcation of SIRS and PeaceWorks a few years ago in no way affects the integrity of Murshid’s work as a whole. Murshid himself would have taken the same steps and incorporated the Dance work separately as an educational non-profit organization, just as Saadi did, so that restrictions as to grant aid and other practical considerations would not be as stringent as they are with SIRS, which is a religious non-profit organization” (letter, November 28, 1989).

During this period, largely through volunteer effort and self-funding by the key teachers, the Dance work quickly began to expand internationally. The Dance Center sponsored a citizen diplomacy trip to Russia in 1989, which led to ongoing support for circles there and an annual training for leaders held in England. In 1990, the Center began the annual “Peace through Arts” camp in England as an international gathering place for Dance teachers and dancers. (It was much easier for both Russians and Europeans to obtain visas to the UK, and travel costs were less.)

The Center also sponsored a Dance peace pilgrimage to the Middle East (Israel, Jordan and Syria) in September 1993, which through sheer synchronicity (or grace) coincided with the signing of the Oslo Accords. During both the Russian and Middle Eastern trips, a disciplined group of Dancers would appear in public places and invite others to join them in dancing for and in peace. Some members would hand out cards in multiple languages explaining to onlookers what was happening. “Peace demonstration dancing” became a feature of this more activist phase of the Dances of Universal Peace work and was repeated in various forms in Atlanta, GA for the Olympics in 1996 as well as in public spaces in Canada, Australia and other places.

As part of the internationalization of the Dances, regional Dance networks were established in a number of countries, along with family or community camps that centered around the Dances and Walks. The first, and longest running, of such annual family Dance camps was established by the German Dance Network (NdL) in 1994, which today includes upwards of 300 adults and young people.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, annual training events continued at the Lama Foundation, as well as in England, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Russia, Australia, Brazil and other countries. Key people who conducted or assisted in these early trainings, along with Tasnim and Saadi, were: Kamae Miller, Amida Harvey, Tansen Philip O’Donohoe, Gita Sophia Onnen, Rahmana Dziubany, Verena Karima Hochheimer, Alima Stoeckel, Michael Stoeckel, Barbara Kung, Zamyat Kirby, Anahata Moore, Matin Mize, Radha Tereska Buko, Noor and Akbar Helweg, Christina Schölziger, Zubeida Mitten-Lewis and Zahira Madeleine Bullock.

Under a model designed by Tasnim and Saadi, these trainings included various components still used today: concentration, visualization, meditation, sound and musicianship, voice, rhythm, walking meditation and body awareness. Spiritual practices from the (primarily) Sufi as well as Buddhist and Hindu traditions were interlaced with practical training in technique. For the first time, the trainings included the use of small ‘practice’ circles in which both beginning and intermediate dance leaders could receive feedback in a supportive atmosphere. A key feature of the original training model included the history of the Dances of Universal Peace “ancestors”—Murshid Samuel Lewis, Hazrat Inayat Khan and Ruth St. Denis. Some experience in Ruth St Denis’ creative meditations for ‘picking dances from the cosmos’ was also included. As part of the process of acknowledging the ancestors, in 1986 the SIRS published the book Sufi Vision and Initiation, the collected autobiographical writings of Murshid Samuel Lewis, edited by Neil Douglas-Klotz. To acknowledge and support the understanding of Ruth St. Denis’ role in Murshid S.A.M.’s inspiration for the Dances and Walks, in 1997 PeaceWorks published the book Wisdom Comes Dancing: Selected Writings of Ruth St. Denis on Dance, Spirituality and the Body, edited by Kamae A Miller.

In 1992, Saadi and Tasnim wrote the first version of the Dance certification guidelines and charter for the Mentor Teachers Guild (MTG) with the intention of broadening training to include more senior leaders. With the collaboration of other new mentors, the MTG published its ethical guidelines in 1996. In 2003 PeaceWorks produced the first edition of its Foundation Dance and Walks Manual, edited by Radha Tereska Buko, with the intention of providing reliable notation of the original Dances of Murshid Samuel Lewis as well as other foundational mantric Dances, which could be then translated into other languages in countries and regions where the Dances had taken root.

Through the first decade of the 21st century, the international focus for the Dances continued to expand, particularly moving into other countries in South America as well as Central and Eastern Europe. This necessitated other organizational name changes, including the International Network for the Dances of Universal Peace and presently Dances of Universal Peace International. The board of trustees also became international, while at the same time the organization returned to its grassroots model, decentralizing governance to local regions while still providing resources and networking internationally through the greatly expanded capacity of the internet.

Throughout all of the external change, the essential purpose of the group has remained: to allow more people to experience, and share further, the blessings of this deep and potentially transformative spiritual practice left to us by Murshid Samuel L. Lewis. Moving beyond philosophy to experience, the Dances remain one of the earliest and most potent expressions of the interspiritual impulse in the world, motivated by the human soul’s increasing compassion for all beings.